KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, US — As mid-year approaches, volatility and uncertainty are the key characteristics of dry bulk shipping markets. International grain supply chain stakeholders can expect more of the same during the rest of 2023.

Geopolitical turmoil continues to cast a dark cloud over shipping (and grain) supply and demand forecasts. Certainly, relations between the United States and China remain harried, at best, while Russia’s destructive and tragic invasion of Ukraine shows no sign of being resolved any time soon.

Recessions, albeit shallow ones, threaten Europe and the United States. And the recovery of China after COVID lockdown controls were rapidly removed has been underwhelming.

Shipping price slump

Economic positives might be in short supply, but grain shippers can take succor from low shipping costs and the expectation that, while fluctuations are forecast, the upside for charter and spot markets is limited.

By any measure, bulk carrier owners and operators have seen returns tumble over the last year. The International Grains Council (IGC) Grains and Oilseeds Freight Index stood at 128 on May 30, down 44% compared to a year earlier.

"Close monitoring of all factors with the capacity to affect the freight markets is essential in order to manage risks effectively." - Plamen Natzkoff, NSI

Even more strikingly, the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), an index of average prices paid for the transport of dry bulk materials across more than 20 routes, stood at 1,295 on May 24. Although this represented a major increase from the bottom-crawling levels of February when the BDI dropped consistently below 600 points, it was significantly lower than the 3,253 recorded on May 24, 2022. Likewise, the Baltic Handysize Index (BHSI) in late May was hovering around the 600 level, almost three times lower than a year earlier.

Slowing demand was the main drag factor on shipping prices in late 2022 “as the global economy struggled with fears of recession, the outbreak of war and extended lockdowns in China,” explained Drewry analyst Tanvi Sharma.

More recently, large numbers of bulk carriers have re-entered the open market following the ending of lockdowns in China, which enable ports to normalize operations and whittle away the queues of vessels that had been stuck at congested bulk terminals.

“One of the main reasons for the historically record-high rates in late 2021 was port congestion,” said John Kartsonas, managing partner, Breakwave Advisors.

“As such inefficiencies subside, the normalization of trade means looser market balance for ships and thus lower freight rates,” he said. “Of course, congestion remains a major factor when it comes to vessel supply, and bad weather, port strikes and other related factors will continue to play a role. But the disruption around COVID-19 measures was major, and now it has come to an end.”

Vessel supply versus demand

Sharma said general bulk carrier demand will grow by around 4.5% this year, 4% in 2024 and 3% in 2025. Overall demand therefore will be marginally outstripped by supply as the rising numbers of newbuild deliveries see the bulk carrier fleet expand by around 5% this year.

Even so, the orderbook for the smallest vessels is low by historical standards. The Handysize orderbook is currently just 3% of the overall Handysize fleet, while the Supramax orderbook is 7% of the fleet and set to drop yet further in the next two years.

“While the orderbooks for those sectors have been relatively low for four to five years now, the last time there were so few vessels on order was in the late 1990s,” Plamen Natzkoff, associate director for Dry Bulk Commodities at shipping consultancy MSI, told World Grain. “With relatively few vessels due to be delivered over the next few years, a strengthening of the demand for those vessels is likely to be highly positive for (ship owner) earnings. It is worth noting that such an increase in the demand for vessels does not necessarily require a significant pick-up in the demand for particular commodities. Changes in vessel operations associated with environmental regulations or increases in port waiting times can also lead to positive earnings surprises.”

Minor bulk bumps demand

The less than capesize categories of ships used by grain shippers will see seasonal volatility in 2023, with rising shipments of steel products, cement, pet coke, fertilizer and forest products putting some upward pressure on rates.

“Another factor that will be a key driver for the smaller vessels is whether cargoes move back into the container trade,” Natzkoff said. “Specifically, as container rates shot up in 2021-22, a range of break bulk cargoes transitioned from container vessels onto geared bulkers. Whether they now move back into the container trade will be important for the bulk carrier market balance.”

The Black Sea

Credit: ©AGRESOURCE CO.

Credit: ©AGRESOURCE CO. How much sway grain movements have on wider bulk markets this year will in part be determined by geopolitics. As World Grain was published in mid-June, not only was the EU blocking some Ukraine wheat exports, but Russia was threatening not to abide by the two-month extension of the Black Sea grain deal it agreed to in May, blaming Ukraine for the damage suffered in June to an ammonia fertilizer export pipeline that runs through Ukraine.

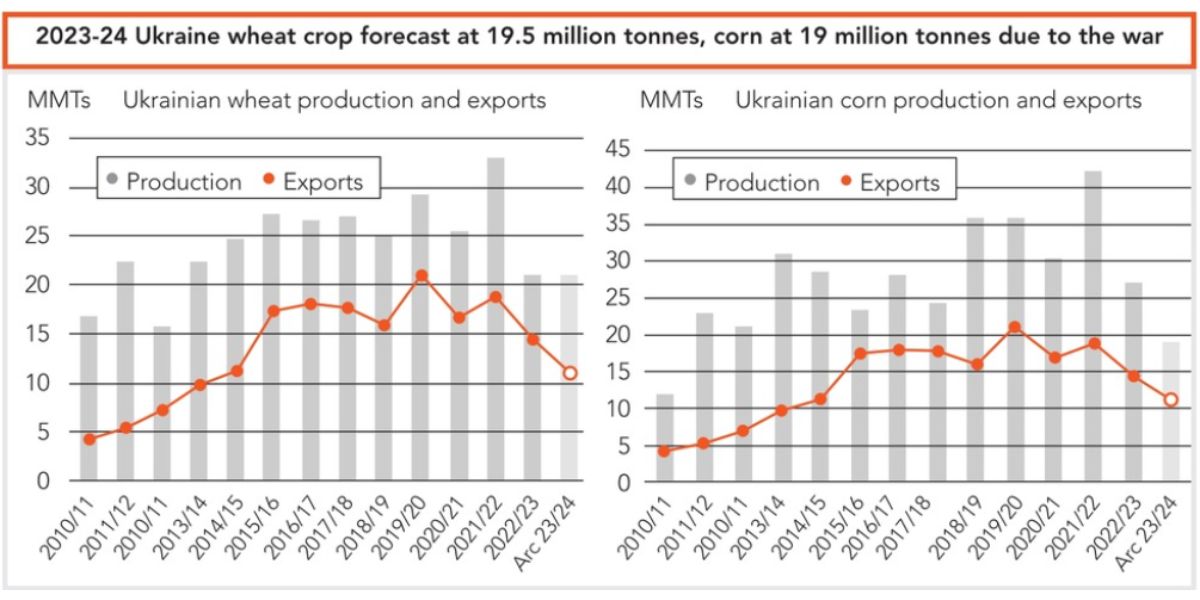

Dan Basse, president, AgResource Company, expects Ukraine’s 2023-24 wheat exports to total just over 11 million tonnes, representing a steady decline from the almost 20 million tonnes recorded in the 2021-22 season. Corn production and exports also have been decimated by war (see above chart).

Even though China’s economy is “spluttering,” Basse expects its soybean imports alone to total around 101 million to 105 million tonnes, although the United States is predicted to lose market share to Brazil.

The International Grains Council (IGC) expects total grains trade in the 2022-23 (July/June) season to total 411 million tonnes, down from 424 million tonnes a year before, a drop mainly due to a contraction in maize volumes. Trade in sorghum and, to a lesser extent, barley, is also set to decline, more than offsetting an expansion in trade in wheat, said Darren Cooper, senior economist at the IGC.

Logistics bottlenecks

Turning to global grain logistics bottlenecks, Alex Karavaytsev, senior economist with the IGC, said Brazil had faced increased pressure on inland logistics earlier this year ahead of what was expected to be a record soybean crop.

“This was compounded by rain-related shipping delays from the main ports,” he said. “While the situation has somewhat improved recently, increasing domestic production of grains and oilseeds continues to test the limits of inland logistics, which remains heavily reliant on truck transport, which accounts for up to two-thirds of grains and oilseeds volumes.”

Karavaytsev also reported some bottlenecks for imported soybeans at Chinese ports “in part owing to customs delays and increased inspections of cargoes,” while long vessel queues, including for wheat cargoes, had been recorded in Iran “amid payment issues.”

However, turn-of-the-year port congestion at Egypt’s ports had cleared by mid-May, while “significant improvements in port throughput capacity have been noted in Australia over the past couple of seasons, which will allow the country to reach new records in terms of grains exports.”

US grain exporters: Planning ahead

Grain exports from the United States helped to fill gaps in the market in 2022 as exports from Ukraine contracted due to the war, and because sanctions on Russian banks hampered its wheat exports. The IGC expects US wheat exports to be their lowest in more than 50 years in the current season due to domestic production trending lower and local supplies losing out to international competition.

“This season, prices for hard red winter wheat have been underpinned by worries about lingering drought conditions in the US Plains, while spring wheat prices drew support from concerns about weather-related planting delays,” Cooper said.

Pricing forecast

Drewry’s Sharma also expects US grains exports this year to be “subdued,” not least as China is diversifying its sourcing.

“We therefore expect a decline in the time charter rates of both Supramax and Panamax segments in 2023, in which most of the grain is shipped,” she told World Grain. “With regards to the trip rate from the US Gulf to Europe, the US-dollars-per-day cost more than halved year-on-year in (first quarter 2023). There will be a marginal uptick in the upcoming quarter as the rates in (first quarter 2023) usually remain subdued in the dry bulk market. However, the annual trip rates on this route in 2023 will be lower as compared to 2022.”

As for bulk carrier shipping pricing more generally, Sharma forecasts that charter rates already have bottomed out and will strengthen in the second quarter as Chinese demand revives. For his part, Natzkoff suggests that grain shippers should plan for ups and downs throughout the rest of this year.

“A notable feature of the past one to two years has been the increase in the volatility of freight rates,” he said. “Not only that, but the availability of vessels and port-side facilities themselves at short notice has at times been limited.

“While the last couple of months have seen freight markets that are somewhat more staid, the sharp movements in freight rates that we saw at the start of the year suggest that any one of a variety of catalysts has the potential to bring about renewed bouts of volatility.

“With this in mind, close monitoring of all factors with the capacity to affect the freight markets is essential in order to manage risks effectively.”

Michael King is a multi-award-winning journalist and podcaster as well as a shipping and logistics consultant. He also supplies an array of corporate services. For more information, email mikeking121@gmail.com.