BEIJING, CHINA — It is home to 20% of the global population while accounting for only 10% of the world’s arable land, and despite having a stated goal of becoming self-sufficient in grain by 2032, it has increased imports of corn, wheat and soybeans by twelvefold over the last five years.

This country, of course, is China, and no nation in recent years has been more aggressive, both domestically and abroad, in addressing its food security issues.

To increase domestic grain production, China has done the following:

- Reconsidered its position on genetically modified corn and soybeans and is on a path toward adopting GM seed technology.

- Recently approved the safety of a gene-edited soybean variety.

- Urged farmers to plant narrower rows of corn and other crops and to double-crop wherever possible.

- Provided greater financial incentives for farmers to plant soybeans to attempt to lessen its dependence on imports.

It even appears that China’s well-intended push to increase domestic soybean production may be negatively impacting output of other crops and the profitability of its farmers.

Even if all those plans are successfully implemented, it’s doubtful China can feed itself with corn and soybean yields currently estimated at 60% below that of the United States and with acreage so limited.

It even appears that China’s well-intended push to increase domestic soybean production may be negatively impacting output of other crops and the profitability of its farmers. In recent years, more farmers are planting soybeans, which at this point are lower yielding and less profitable than crops such as corn and wheat. That could change if China decides to fully commit to genetically modified soybeans, but for now it may be contributing to a shift toward more imports of wheat and corn.

In the past three years, China has imported 29 million, 21 million and 18 million tonnes, respectively, of corn. Prior to the 2020-21 marketing year, the record for corn imports was 7.5 million tonnes. China has followed a similar pattern with wheat, importing 10.6 million and 9.5 million tonnes in 2020-21 and 2021-22, respectively, and an estimated 12 million tonnes this year, which would be a record. Prior to that, the record for wheat imports was 6.7 million tonnes in 2013-14.

Steve Nicholson, global sector strategist for grains and oilseeds at Rabobank, said in terms of consumption strategies, China is trying to reduce the volume of soybeans required for feed production.

“They are making changes in their feed rations for their swine herd,” Nicholson said. “They had been using 12% to 15% (soy meal) inclusion in their rations but basically want to cut that in half, which will require fewer soybeans.”

While the rhetoric of the Chinese government is focused on self-sufficiency, the message is somewhat contradicted by a slew of investments in infrastructure and farmland in foreign countries.

“If they are going to be self-sufficient, why would they be investing overseas in places like South America and Africa?” Nicholson asked. “That’s a head scratcher to me. There’s a reason they are making investments in those places. They need land to produce for their population.”

Hedging its bets

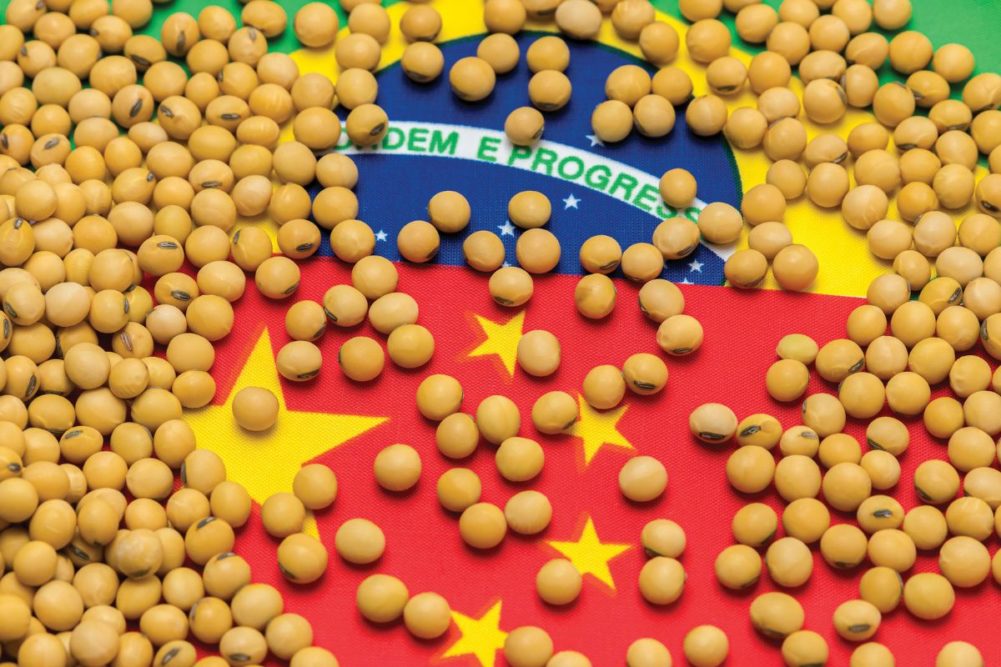

China has hedged its bets on self-sufficiency with overseas investments, most notably in Brazil, the largest producer and exporter of soybeans by a margin that has been increasing each year. Brazilian soybean production has nearly doubled over the last 10 years from 82 million tonnes to 154 million, according to the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) of the US Department of Agriculture. Exports have more than doubled from 41.9 million tonnes to 92.7 million during that time.

By contrast, China is estimated to produce 20.2 million tonnes of soybeans in the 2022-23 marketing year. Although that would represent a 53% increase from 10 years ago, it still accounts for only 18% of what it annually consumes.

With the Chinese having already invested several billion dollars into upgrading Brazil’s agricultural infrastructure and through land purchases, Brazilian officials are courting a fresh round of investments from COFCO, a Chinese state-owned agribusiness and one of the world’s largest grain traders, according to recent media reports.

According to COFCO, Brazil accounts for more than 40% of the company’s global investments and two-thirds of its 11,000 global staff are based there. COFCO already has invested in Santos, Brazil’s top soybean port, and currently is expanding its export terminal capacity to 14 million tonnes to help it feed China’s voracious demand for soybeans.

China also has made major agricultural-related investments in Africa, although a full return on investment likely won’t be realized for many years, Nicholson said, due to chronic problems with political and economic stability. But with a large amount of untapped or underutilized arable land, the long-term potential is there.

“Keep in mind that China views return on investment differently than, say, the United States,” Nicholson said. “They are a state-owned operation. Would a US grain company go someplace and lose money for 10 years? Probably not. They’ll do it for a bit and see if it works, but if it doesn’t work over a longer period of time, they will pull up stakes.

“The Chinese don’t have the same hurdles that the ABCD’s (ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus) do, or any other privately or publicly-owned agribusiness company has. They are long-term thinkers. They believe that eventually it will work out and they’ll be repaid those dividends at some later date.”

©MICROONE - STOCK.ADOBE.COM

©MICROONE - STOCK.ADOBE.COMBelt and Road Initiative

Another expensive venture designed to bolster China’s food security is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013 by Xi, the vast collection of development and investment initiatives was devised to link East Asia and Europe through physical infrastructure. Since then, China has signed agricultural and fishery cooperation documents with more than 80 countries, and more than 650 agricultural investment cooperation projects have been carried out in countries along the Belt and Road.

“The Belt and Road region, with its vast territory and rich agricultural resources, is an important area for China’s agricultural cooperation and trade and plays a significant role in ensuring food security and agricultural product safety,” Ma Lili, of the School of Economics and Management at Northwest University, said on a Chinese government website.

Ma said the BRI has created favorable conditions for agricultural cooperation in terms of connectivity, trade and investment facilitation, monetary integration, and promotion of exchanges.

The construction and connection of large markets will help countries and regions along the route to carry out a differentiated division of labor, promote specialized production, and expand competitive advantages; the exchange and cooperation in the field of agricultural science and technology will help share knowledge and improve the efficiency and quality of agricultural production, Ma said.

According to data from the General Administration of Customs, in 2021, China imported 326.55 billion yuan (about $47.84 billion) of agricultural products from the BRI countries, an increase of 26% year-on-year.

Nicholson said although the BRI is still part of the equation in China’s food security, he noted that some countries “have become a little more skeptical of it because it loads them up on debt that they owe China.”

“Because of the higher interest rates and the stronger US dollar, compared to other currencies, that debt will be that much more expensive,” he said. “So, I do think there’s a little more caution from countries about jumping on board but it’s still in the works.”

Pragmatic buyers

Although growing geopolitical tension between China and the United States, which traditionally has been one of China’s biggest grain and oilseed suppliers, led to a trade war that lasted nearly two years toward the end of the 2010s and the recent rejection of China’s plan to build a corn mill in North Dakota, Nicholson said the decision whether to purchase US soybeans, corn or wheat ultimately will come down to price.

“China is extremely pragmatic and will do what’s good for them in the end." - Stephen Nicholson, Rabobank

He noted that China’s announcement in late April that it was canceling the purchase of 560,000 tonnes of US corn was likely a price issue, not a political one.

“If there’s a price-sensitive customer in the world, it’s the Chinese,” Nicholson said. “They’re not canceling the contracts because they don’t want US corn; they just don’t like the price. If the price gets cheap enough, they’ll come back and buy it.”

With Brazil and Argentina increasing corn production and China strengthening its political and economic ties to that region, US grains and oilseeds farmers — particularly soybean producers — have become concerned about potentially losing a significant share of the Chinese market in the coming years. Even with the billions of dollars it has invested in agricultural land and infrastructure in South America, Nicholson believes that when US soybeans are the cheaper option, China won’t hesitate to shift back.

“China is extremely pragmatic and will do what’s good for them in the end,” Nicholson said.

To the Chinese government, that means a well-coordinated effort to increase domestic grains and oilseeds production while also strategically linking itself to as many foreign sources of agricultural products as possible.