Drought continues to linger from eastern and southern Canada’s Prairies through the majority of the western United States into Mexico. This region has seen little to no improvement in drought status since last autumn, which is not a good sign for spring and summer. Spring precipitation in these areas is an absolute must. Without the moisture the region is destined to heat up very quickly during the late spring and summer, translating into greater potential for high pressure to build aloft sooner and more intensely than usual. Temperatures this spring will become a critical indicator of what may lie ahead for US crop areas.

Do you remember 2012? That was an amazing drought year in the United States that was equal in intensity and breadth to that which occurred in 1934. The drought was more serious than the drought of 1988, which had long been heralded as the worst drought in the nation since the 1950s. The drought of 2012 began with warmer-than-usual temperatures occurring in January and February in an environment that was already quite dry in the southern Plains, upper Midwest and southeastern states as well as in the western United States. It was a year in which a moderate La Niña diminished to neutral ENSO conditions between January and May (similar to the forecast for this year’s La Niña), but that La Niña had been around since summer 2010 and had been a moderately strong event at times.

The difference between the La Niña of 2012 and the current weather pattern is that this year’s event has only been around since late last summer. The drought of 2012 culminated after almost two years of atmospheric dominance by La Niña, which had the atmosphere drier than it is now, but there are still similarities between the two years. This year’s cold snap in February was in direct contrast to the otherwise warm winter weather of 2011-12, but the reason for it was the result of sudden stratospheric warming and not a part of a prevailing weather cycle. If February 2021 is removed from the winter months, temperatures anomalies for November through January of both 2011-12 and 2020-21 are similar enough to raise a few eyebrows.

However, drought intensity based on the Palmer Drought Severity Index in January 2021was most significant in the western half of the United States except for Montana and South Dakota, which were not in a Palmer Drought. There were also pockets of drought in North Dakota, Iowa, eastern Nebraska and the southern Great Lakes region and the northeastern states. In January 2012, drought was not nearly as intense in the western United States, but it was more serious in the southern Plains and in the upper Midwest as well as the southeastern states. The status of drought leading into the spring of 2012 was already harsher in major crop areas than it is today.

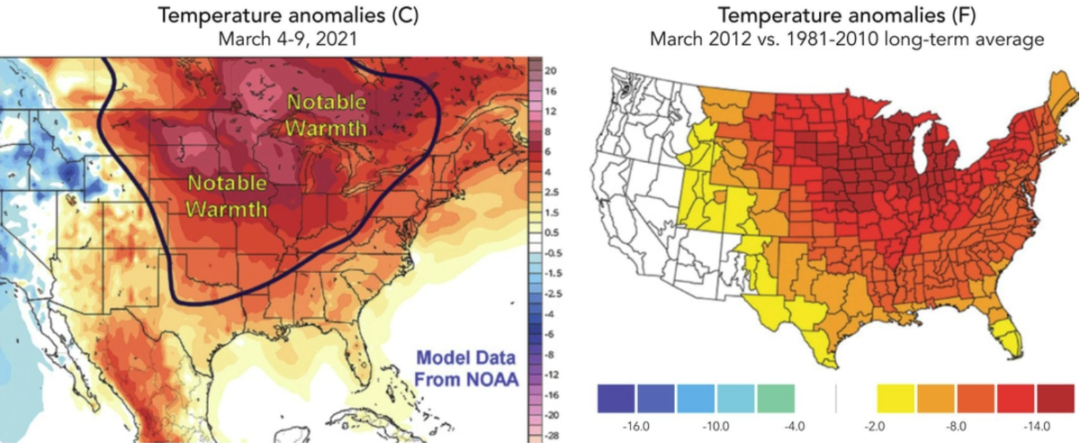

It was the heat that quickly pushed key US crop areas into expanded drought during the spring of 2012. March temperatures were well above average in the Great Plains, Midwest, Delta and most Atlantic Coast states. Departure from normal readings varied from 8 to more than 15 degrees in many of the areas noted above. The heat exacerbated the dryness that was already present in parts of the upper Midwest, Southern Plains and southeastern states and drying was quickly expanding with each of the drought-stricken areas merging into the other areas. Another warmer-than-usual month of weather occurred in the Great Plains, western Midwest and Rocky Mountain region in April 2012. That was enough to overpower the precipitation that fell during the two months resulting in a drought that was beginning to feed upon itself evaporating moisture faster than it could fall, and by the end of April much of the nation was in a drought that got much worse in May.

Just enough similarities

There are just enough similarities to the weather in recent weeks and that which is projected over the next couple of months that World Weather, Inc. is becoming more interested in the parallel. Conditions are different enough to prevent the same solution, but some of the mechanics of weather systems in the spring of 2021 will be similar to those of 2012, making the parallel an extremely important one to follow.

The impact of a drought year in the United States and parts of Canada in the current environment would be explosive, to say the least, to commodity futures prices that already have been strong in recent months over worry about US ending stocks for corn, soybeans, and wheat while there is a heightened demand for grain and oilseeds coming from China. Could this become the “perfect storm” that leads to a world food crisis? Probably not. But once the doom-and-gloom forecasters reach such a conclusion the result could be inflationary agriculture prices, the likes of which have not been seen in this lifetime.

With that said, let’s slow this thinking down. Even though conditions are similar, they are also different. Most of the eastern US is not dry and there are only a few pockets of significant dryness present today compared to the first quarter of 2012. That means a heatwave in March would not have the same impact that it had in 2012, but crop areas in the Plains and western Midwest would certainly have potential to trend much drier.

The first signal that must be looked at in determining whether 2021 is going to be another serious drought year is temperatures. How warm it gets in March and where the greatest temperature anomaly is relative to the United States and Canada will have much to say about where dryness will expand to or if it will expand at all. Early March temperatures already are advertised to be extremely warm. The start of March will be a little too much like that of 2012 and worry already will begin with the quick drying that is expected in response to well-above average temperatures.

Some computer forecast models have suggested a warmer-than-usual month of March for much of North America and that could also be a concern. It is important to note that some cooling is expected in the second week of March in Canada and the western United States, but that positioning of cool air will only reinforce the potential for ongoing warmth in the Midwest, Plains, and southeastern states. If the pattern for warm weather does prevail in March and precipitation is not abundant enough in the Plains or western Corn Belt to counter the evaporation rates, then worry over expanding dryness will begin, and if the situation is perpetuated into April and May, all bets are off regarding drought for the remainder of the year.

For now, March 2021 does not look as harsh as March 2012.

Drew Lerner is senior agricultural meteorologist with World Weather, Inc. He may be reached at worldweather@bizkc.rr.com. World Weather, Inc. forecasts and comments pertaining to present, past and future weather conditions included in this report constitute the corporation’s judgment as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice.