Iraq, recovering from the effects of war, faces a new battle with the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. At the same time as controls adversely affect its agrifood production and distribution system, the impact of the crisis on the world economy has hit the value of oil — its one vital export.

The International Grains Council (IGC) forecasts Iraq’s total grains production in 2020-21 at 7 million tonnes, up from 6.5 million the previous year. The wheat crop is predicted at 5.4 million tonnes, up from 4.8 million. Output of barley is forecast at 1.2 million tonnes, down from 1.3 million the year before. The country also is expected to produce an unchanged 300,000 tonnes of rice.

The IGC’s forecast for Iraq’s 2020-21 imports of grain is 3.2 million tonnes, up from 3.1 million in 2019-20. The 2020-21 total includes 2.8 million tonnes of wheat, up from 2.6 million the previous year. Rice imports are seen at an unchanged 1.2 million tonnes.

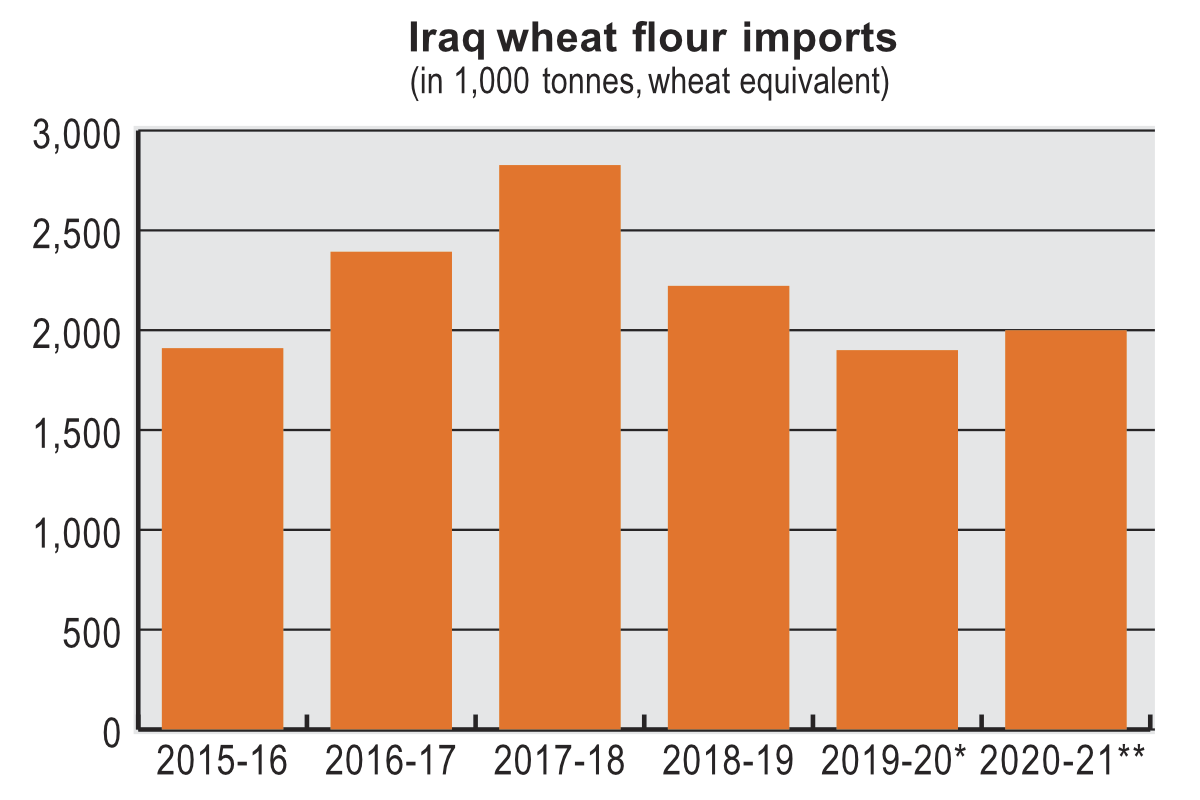

Iraq is a major importer of wheat flour. The IGC puts its 2020-21 imports at 2 million tonnes, up from 1.9 million the year before.

In a Country Brief on Iraq dated May 15, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said that conditions for crop development had been “generally favorable across the country with timely and well-distributed rains.”

“The northern cereal-producing belt of Kirkuk, Nineveh and Al Suleymaniah governorates experienced an early autumn dryness until late November 2019, but abundant precipitation starting from December significantly improved soil moisture content,” the FAO said.

The FAO forecast a 6.5-million-tonne grains crop, compared with its forecast for 2019 of 6.8 million.

The Grain Board of Iraq buys from farmers.

“Despite the pressure on the national budget, reports indicate that farmers are paid in cash upon presenting a letter from the ministry of trade confirming the quantity and amount due,” the FAO said.

By May 9, the state buyer had purchased 542,000 tonnes of wheat.

“The wheat purchased is then used in the Public Distribution System (PDS), which distributes subsidized basic food rations to the population,” the FAO explained. “The total cereal import requirements, despite the expectations of an above-average 2020 domestic harvest, are forecast to be near average, a level similar to the previous year, as the government tries to rebuild stocks that have been recently depleted by the COVID-19-related stockpiling by consumers.”

In a separate analysis of the effects of the pandemic, the FAO said Iraq is vulnerable to the impact of COVID-19 due to pre-existing vulnerabilities, including poverty, dwindling natural resources and ongoing displacement due to past conflicts.

“The collapse of the global oil market in April has also had serious implications for Iraq’s capacity to import food,” the FAO said. “Approximately 90% of the government’s income derives from oil revenue.

“From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government of Iraq has exempted agricultural stakeholders from movement restrictions, allowing them to continue production and transport of agricultural goods.”

However, it warned of challenges to supply chains.

“Unless the constraints facing agricultural supply chains are addressed, food security and job opportunities will be affected,” the FAO said.

In an annual report on the grains sector, the USDA attaché explained Iraq’s system for distributing grain.

“The Public Distribution System was created in September 1990,” the attaché said. “Since then, the system has been updated a number of times. It has consistently provided Iraqis access to a range of staple commodities. In its current iteration, program participants pay 500 Iraqi dinars ($0.42) for each quota of food, which contains shares of flour, rice, sugar and cooking oil.”

The attaché noted that the program allocates nine kilograms of flour eight times per year and allots other staples six times per year.

“The PDS system accounts for a large percentage of Iraqi wheat consumption,” the attaché said.

The attaché put the total amount of wheat distributed under the system at approximately 3.96 million tonnes a year.

“However, there are additional amounts consumed annually in the form of grain or flour, increasing total consumption,” the attaché said. “A large quantity of the wheat flour distributed under the PDS system ends up either as animal feed due to poor quality or because families have no ability to bake the flour.”

Wheat flour milling industry

There are around 300 privately owned flour mills in Iraq.

“Much of the private sector milling capacity remains underutilized,” the attaché said. “Private sector mills receive wheat supplies after the public sector capacity is filled. Some private millers in the past stopped or limited production due to security concerns. However, this constraint no longer occurs. The Iraqi government retains ownership of wheat and products throughout the production process.”

In April 2019, nine flour mills began milling 72% extraction (fine) flour for sale in the Iraqi market, the attaché said. Prior to this change, the only fine flour available in the Iraqi market was imported from Turkey, Iran, Kuwait or Jordan as Iraqi mills produce only 80% extraction flour.

“Iraq continues to import sizable volumes of wheat flour from Turkey, Iran, Kuwait and Jordan,” the attaché said. “Traders estimate that around 85% of flour imports are Turkish, while the remaining 15% comes from other countries. Reportedly, around 100 Turkish mills are producing only for the Iraqi market. Turkish millers produce specifically for the Iraqi market and label products in Arabic as per the buyers’ specifications.”

As the Iraqi population is beginning to consume more barley bread over wheat bread for dietary reasons, some wheat flour imports from Turkey are being replaced by barley flour, which is becoming an important source for bread in almost all private sector bakeries, the attaché said.

“Turkish millers sell flour to Iraqi importers on credit, which is paid on a weekly basis after the product is sold,” the report said. “Turkish flour prices are reportedly competitive and stable, in spite of wheat market fluctuations.

“As crossings are limited in the mountainous border region, an advanced logistics and shipping system has developed around the city of Zakho. Reliable statistics on cross-border trade are not available and large volumes of unregistered product are likely flowing to Iraq from both Iran and Turkey.”

Other grains

The attaché put 2020-21 barley consumption at 1.685 million tonnes.

“Iraqis generally use barley as animal feed for sheep, goats, and beef and dairy cattle, which would compete directly with feed grade wheat,” the report said. “Some breads and other dishes for human consumption are produced with barley. However, barley in this case is mostly imported from Turkey and the volumes are low.”

According to the attaché, corn production has been increasing because of rises in yield and area, with agriculture ministry promoting higher yielding hybrid varieties, mostly imported from the United States. Consumption is predicted at 720,000 tonnes in 2020-21.

“Corn in Iraq is mainly used by poultry feed mills, but the use of corn by the aquaculture sector is also increasing,” the attaché said. “Traders supply most imported corn to feed mills. Feed mills prefer imported corn, especially South American origin, due to the quality, moisture rate, and low occurrence of aflatoxins.”

Rice production was briefly prohibited in 2018 in the face of drought, as officials diverted supplies to drinking water, industrial uses and horticulture, the attaché said.

The report put 2020-21 consumption at 1.6 million tonnes, with around 720,000 tonnes distributed through the public system.

“Currently, program participants receive three kilograms of rice every two months,” the attaché said.

Private firms also mill domestic rice and sell it on the local market.

“Long-grain variety Basmati rice is mainly imported from India via UAE,” the attaché said.

Chris Lyddon is World Grain’s European correspondent. He may be contacted at: chris.lyddon@ntlworld.com.