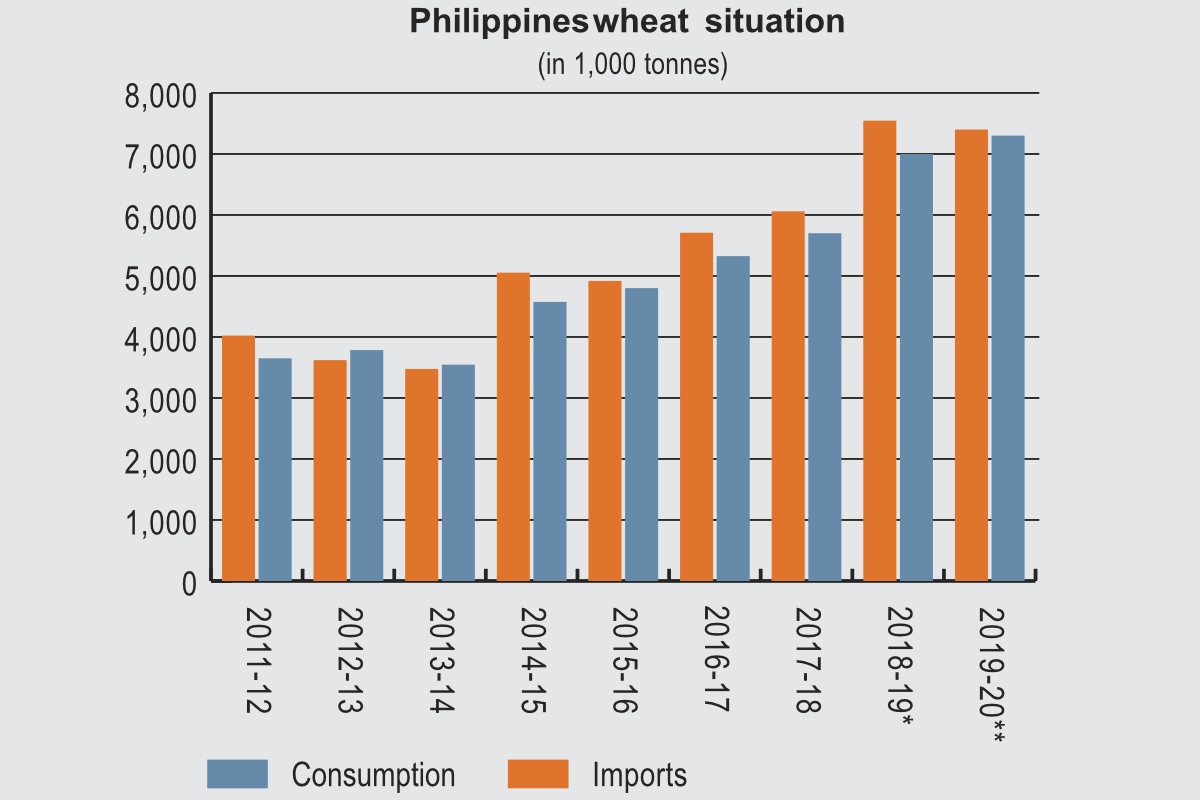

The Philippines produces no wheat, but wheat flour is increasing in importance in the diet of its people with growing affluence, making the country a major importer, particularly from the United States. Rice remains the main staple of its people’s diet. With a large pork producing sector, the Philippines is also the biggest market for U.S. soymeal, as well as having a large feed producing sector of its own.

In its September Grain Market Report, the International Grains Council (IGC) forecast the total grains production of the Philippines in 2019-20 at 8.3 million tonnes, a figure unchanged from the previous month, up from 7.7 million in 2018-19. All of it is maize.

Total grains imports are forecast at 8 million tonnes, an unchanged estimate, down from 8.3 million the year before. Wheat imports are put at 7.5 million tonnes, another unrevised figure, down from 7.7 million the year before.

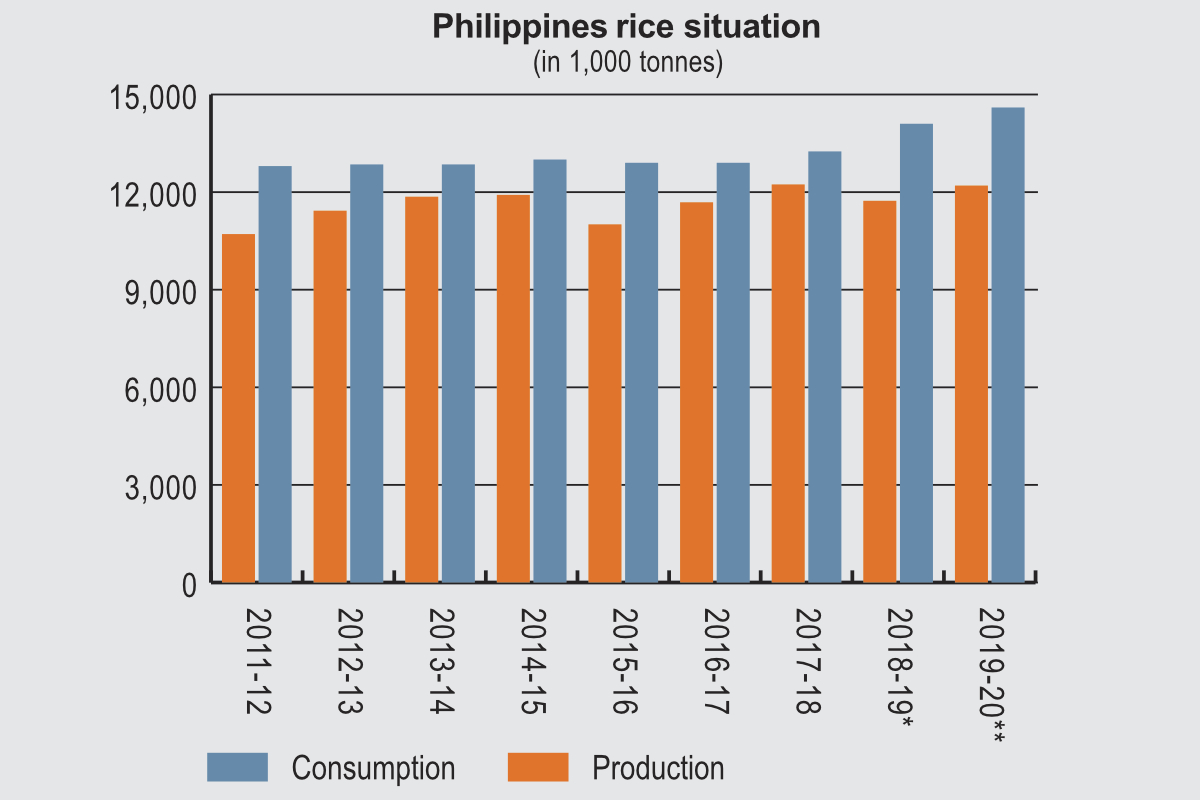

Philippine production of rice is forecast at 12.6 million tonnes in 2019-20, unrevised from the previous month’s report and up from 12.5 million the year before. Rice imports in 2019-20 are put at 2.8 million tonnes, compared with 3 million in 2018-19

The country is set to import 3.1 million tonnes of soymeal in 2019-20, another unchanged estimate, compared with 3 million the previous year.

“With no commercial production of wheat or ‘small grains’ in the Philippines, the country is a major importer of milling quality wheat and the United States is its largest supplier,” the USDA attaché said in an annual report on the grains sector. “Rising incomes and a rapidly growing population have resulted in changing diets toward more wheat and protein.

“Rice remains the main staple, however, and its consumption will in fact increase through 2019-20 when factoring in the considerable losses from post-harvest handling and natural calamities.

“Philippine agricultural output is largely a function of weather. The Philippine climate is either tropical or subtropical (in higher-altitude areas) characterized by high temperature, oppressive humidity, and plenty of rainfall.”

Flour milling

According to the attaché, the domestic flour milling industry is increasingly becoming more competitive. A new mill was commissioned in 2018-19, putting the number of mills in the Philippines at 21, with an aggregate capacity of over 5 million tonnes and utilization over 50%.

Bakery products account for about half of milling wheat consumption.

“This includes pan de sal and its derivatives (local salt bread consumed as a breakfast muffin), loaf bread, buns and rolls, cakes and pastries, and Chinese steamed buns,” the attaché said. “The other half of milling wheat demand is for producing noodles, cookies and crackers, and pasta.”

The report added, “Low flour and bread prices, high rice prices, and shifting diets among the burgeoning middle class have kept per capita demand growing at an extraordinary rate. Euromonitor population data indicate a growth in per capita wheat foods from 23.1 kilograms in 2014 to 33.7 kilograms in 2019, a 45% increase.”

The attaché cites figures showing the number feed mills at around 3,000, with production at around 17 million tonnes. Demand for feed maize is expected to rise to 6.7 million tonnes in 2019-20, while feed consumption is seen at 2 million tonnes and falling.

“The domestic feed milling industry continues to consolidate and modernize, servicing the feed needs of the growing livestock, poultry, and aquaculture industries,” the attaché said in its report. “Corn is the preferred feed grain by local end-users. However, quality issues (i.e., aflatoxin) are commonly associated with locally produced corn, and as a result, most feed mills prefer imported corn for its reliability and uniformity.”

Feed producers also import wheat as a maize substitute. The hog sector, which accounts for 60% of feed consumption, is concerned about the presence of African swine fever in Southeast Asia and is pushing for stricter quarantine and import inspection procedures.

“Rice is the main staple of the Philippine population,” the attaché said, noting that rice accounts for an estimated 45% of the average Filipino’s calorie intake and the cost takes up about 20% of the average household budget.

Trade policy

According to the attaché, anti-dumping duties on imports of wheat flour from Turkey will expire on Jan. 8, 2020. The duties took effect on Jan. 9, 2015.

On Feb. 14, 2019, President Duterte signed a law into force replacing quantitative restrictions in rice imports with tariffs. The attaché believed that the new law will mean increased imports from Association of Southeast Asian Nations member countries, particularly Thailand and Vietnam.

The National Food Authority describes its job as “ensuring the food security of the country and the stability of supply and price of the staple grain-rice. It performs these functions through various activities and strategies, which include procurement of paddy from individual bonafide farmers and their organizations, buffer stocking, processing activities, dispersal of paddy and milled rice to strategic locations and distribution of the staple grain to various marketing outlets at appropriate times of the year.”

Oilseeds consumption

The attaché, in an annual report on the oilseeds sector, said “the Philippines is the largest market for U.S. soybean meal,” predicting that U.S. meal would continue to dominate the market, with reduced competition from Argentina and Brazil.

“Philippine soybean production is negligible, and the small amount of imports is purchased largely by a lone crusher,” the attaché said.

“Soybean imports will increase 25,000 tonnes, to 265,000 tonnes in 2019-20, with over 80% expected to come from the United States,” the attaché said. “Expanding imports will be driven by increasing preference for full-fat soybean for feed use, based on prices. Less competition from Brazilian beans is expected as some farmers have reportedly resorted to hoarding due to lower port premiums, weak prices, and the relatively stronger Brazilian currency.”

Local soybean oil production and trade are insignificant due to the local preference for coconut oil (CNO) or palm oil (depending on price), the attaché said.

Coconut oil is the Philippines’ biggest agricultural export. The attaché forecasts a fall in 2019-20 production to 1.66 million tonnes, from 1.71 million the year before, “as coconut trees experience a downward cyclical period.”

Biofuels production

In a November 2018 report on biofuels in the Philippines, the attaché said that ethanol production using sugarcane and molasses in 2018 is expected to increase to 270 million liters from 235 million liters the previous year as aggregate capacity increases.

“Blending peaked at 10% in 2014 but declined to just over 9% in recent years and will further drop in 2018 due to new taxes on petroleum fuels and motor vehicle sales,” the reportsaid.

Coconut oil is the preferred feedstock for biodiesel.

“Consumption growth is driven by increased diesel use since 2009 with the blend rate peaking at 2.8% in 2016 due to increased motor vehicle sales,” the attaché said. “The planned 5% blend in 2015 has not happened due to high coconut oil prices relative to petroleum fuel.

“The Philippine Department of Energy, in its latest energy plan has recommended maintaining the current ethanol and biodiesel blends (10% and 2%, respectively) through 2019, and revisit blend targets through 2040 due to feedstock concerns and pricing.”