Ethiopia is dominated by the agriculture sector, which is responsible for more than 70% of the country’s employment. Grain production is focused on supplying domestic needs, but the country’s growing oilseeds sector is an important export earner.

The International Grains Council (IGC) puts Ethiopia’s total grains production at 21.1 million tonnes in 2019-20, a figure unchanged from its previous estimate as well as from the previous year’s level.

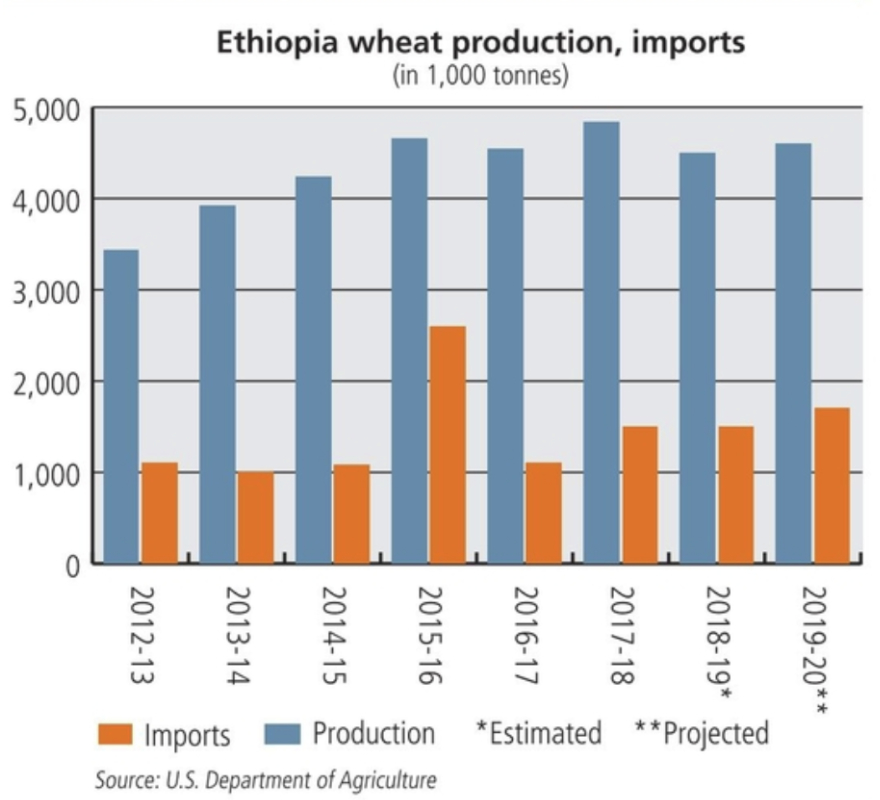

Wheat production in 2019-20 is put at 4.6 million tonnes, unchanged from the previous month’s forecast and up from 4.5 million in 2018-19.

Maize production in 2019-20 is put at 8.1 million tonnes, unrevised from the previous month and down from 8.3 million the year before.

Barley production is forecast at 2.3 million tonnes, unchanged from the previous month and up from 2.2 million the year before. Sorghum output is projected at 5 million tonnes in 2019-20, unrevised from the month before and the same level as in the previous year.

Ethiopia’s total imports of grains for 2019-20 are put at 1.2 million tonnes, a figure unchanged from the forecast made a month earlier and the same level as 2018-19.

The IGC forecasts imports of wheat in 2019-20 at 1.1 million tonnes, unrevised since the previous month’s report, compared with 1.2 million in 2018-19.

In an annual report on the grains sector dated March 29, the USDA attaché noted that forecast 2019-20 output would be a record and looked at the reasons.

“The government of Ethiopia (GOE) focused more on food security programs; there was favorable rainfall distribution during the short (belg) and the long rainy seasons (meher), better input supply, and availability of farm machines for rent for small scale farmers,” the report said.

The report explained that grains are an essential part of the diet of Ethiopians, providing an average of 50% of calorific intake.

The government maintains a ban on exports, although the attaché said “some informal trade is occurring in grain producing areas located along the borders, depending on the production situation of the neighboring countries.”

“Grain imports are exclusively limited to wheat,” the report said. “The Ministry of Trade and Industry, Ethiopian Trading and Business Corporation (ETBC) and Public Procurement and Property Disposal Service (PPPDS) controls wheat imports, except food aid, and oversees bread subsidy schemes.

“Only designated flour mills, mostly in and around the capital city, can buy the subsidized wheat from the government at a discounted price, mill the wheat, and then sell flour at a fixed price to selected bakeries in Addis Ababa and surrounding towns.”

According to the attaché, there are more than 600 flour mills in the country, with a total production capacity of around 4.2 million tonnes of wheat flour a year. A third of them are located in or around Addis Ababa.

“Mills are able to obtain wheat through two channels: subsidized government wheat and domestic wheat on the open market, whose price is higher than the subsidized import price,” the report said.

“Wheat is used to make important traditional staple foods like local bread, porridge (genfo), local beer (tela), roasted grain (Kolo) boiled grain (nifro), pasta, and different confectionery products,” the attaché noted in its report.

The report also said the government subsidizes wheat imports and sells to contracted large flour millers who sell flour to bakeries at fixed prices.

“The goal is to make bread more affordable for the poor at a capped price,” the report said.

Most millers operate at 50% below designed capacity primarily because of reduced supply of subsidized wheat from the government and frequent electric power interruptions, the report said.

Grain production

According to the USDA attaché, there are some 9 million small land holders involved in the production of maize in Ethiopia. Larger commercial farms have been helped to achieve better yields by the increased availability of hybrid seed.

Although 90% of maize in the country is used as food, demand for maize for animal feed — especially for poultry — is increasing.

Sorghum is grown by around 4.8 million smallholder farmers, described by the attaché as “resource poor” and working “typically under adverse conditions in the eastern and northwest parts of the country where the weather is dry with poor fertility and high soil degradation.”

The crop accounts for about 10% of households’ calorific intake in eastern and northwest areas of Ethiopia.

“About three-quarters of the sorghum grain in Ethiopia is used for making injera (the traditional bread),” the attaché said. “Another 20% goes to feed and local beer production, with the remainder held for seed.”

Demand for barley has increased as the result of the construction of a new beer factory.

“Two of the world’s largest breweries, Heineken and Diageo, are working with farmers to produce malt barley for their industries,” the attaché said.

Oilseeds production

The attaché explained in a report dated June 14, 2018, that oilseeds play an important role in Ethiopia’s exports. The biggest export oilseed is sesame, followed by Niger seed and soybeans.

The attaché put 2018-19 soybean production at 120,000 tonnes, noting that output has risen from 35,000 tonnes in 2011-12.

“Most of this growth in production was due to an increase in the area planted, especially from commercial farms, which are few in number,” the report said. “About half of total soybean production is said to come from these bigger commercial operations, some of which are rotating or inter-planting soybeans with other crops. Improved yields also contributed to production increases.”