With a massive population and growing economy, China is a hugely important player on the world’s grain and oilseeds market, notably as the world’s largest oilseeds importer.

The International Grains Council (IGC) forecasts China’s total grains output for 2018-19 at 397.3 million tonnes, down from 402.4 million the year before. The figure includes 131.4 million tonnes of wheat, down from 134.3 million in 2017-18. This year’s corn crop is put at 257.3 million tonnes, down from 259.1 million the year before. Barley production is put at 1.8 million tonnes, down from the previous year’s 2 million. The 2018-19 sorghum crop is put at 3.1 million tonnes, down from 3.3 million the previous year. China is slated to produce an unchanged crop of 500,000 tonnes of oats and an unchanged rye crop of 600,000 tonnes.

China’s rice crop in 2018-19 is forecast at 148.5 million tonnes, down from 148.9 million estimated for 2017-18.

In 2018-19, the country is forecast to produce 16 million tonnes of soybeans (up from the previous year’s 15.3 million) and 13 million tonnes of rapeseed (down from 13.3 million.)

The IGC forecasts China’s total 2018-19 grains imports at 17 million tonnes, down from 22.1 million the year before. The country is seen exporting a total of 500,000 tonnes of grain, unchanged compared with 2017-18.

Forecast 2018-19 imports include 4 million tonnes of wheat, up from 3.7 million tonnes the year before. Wheat exports are forecast at an unchanged 400,000 tonnes.

For maize, the forecast import figure is 4.2 million tonnes in 2018-19, unchanged from the previous year, while for barley, China is expected to import 6.5 million tonnes in 2018-19, compared with 8.7 million in 2017-18.

China is also expected to import 2 million tonnes of sorghum, down from 5.111 million the year before, while exporting 40,000 tonnes, down from 43,000 a year ago. It is also expected to import 280,000 tonnes of oats, down from 419,000 tonnes the year before.

China’s rice imports for January-December 2019 are forecast at 4.5 million tonnes, unchanged from 2018. It is expected to export 2.4 million tonnes in 2019, up from 2.1 million the year before.

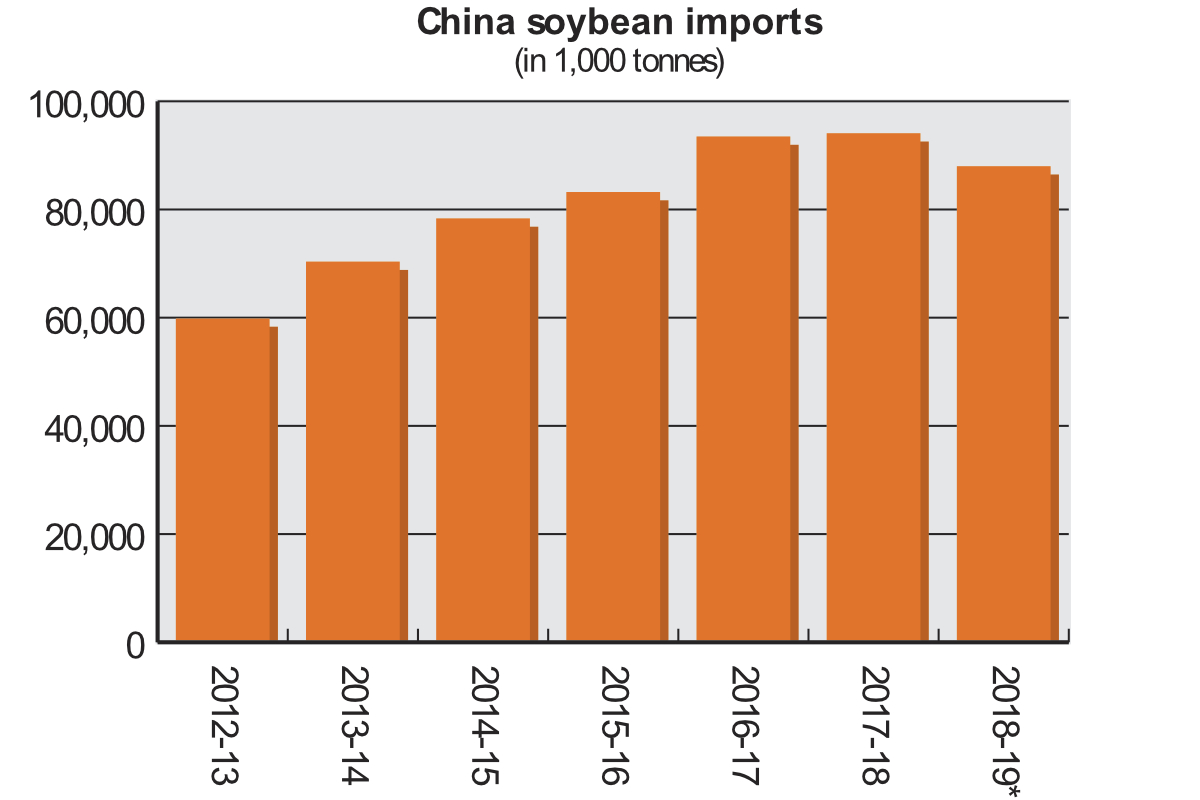

The IGC expects China to import 87.5 million tonnes of soybeans in 2018-19 (October-September), compared with 92 million tonnes the previous year. The country will export an unchanged 100,000 tonnes. It will, according to the IGC, also export 700,000 tonnes of soymeal, down from 1.2 million the year before.

In October-September of 2018-19, China is forecast to import 5.7 million tonnes of rapeseed, up from 4.5 million the previous year.

Farm policy

In an annual report on the grains sector, the USDA attaché characterized the aims of the country’s farm policy.

“China’s agricultural policy-makers manage the dual mandate of ensuring national food security while pursuing poverty alleviation targets, which aim to raise rural incomes through domestic support programs and centrally planned marketing activities,” the report said. “Recent changes to the temporary reserve programs signal that minimum price supports and strategic stockpiles for wheat and rice are expected to continue in the near term. State officials reason that full silos at home will translate into stable prices abroad.”

The report continued, “National agricultural policies swing from risk averse to risk acceptant. At this time, China’s central planners are extremely risk acceptant for new agricultural projects.”

The government is supporting increased corn processing through measures including subsidies in the Northeast. At the time of writing the attaché report, in March 2018, there were “about 20” projects scheduled for completion by the end of 2018, with another 10 yet to break ground.

“When these projects begin operating at the close of 2018, industry analysts estimate an added capacity to process about 20 million tonnes of additional corn a year,” the report said.

Milling industry consolidation

There are over 3,000 mills, according to China’s statistics bureau, although smaller mills are not included and the total figure is not known. The industry is going through consolidation, with more small- and medium-sized mills. Even so, more than half the country’s mills are small, with a daily capacity of 200 tonnes or less.

According to the attaché, industry sources report that flour mills are operating at about 40% capacity nationwide.

“China has experienced a long-term decline in wheat-based staple foods such as noodles and steam breads and a gradual rise in consumption of animal protein products such as meat and dairy,” the report explained. “Demand for instant noodles has declined significantly as steadily rising incomes in urban areas and the emergence of China’s burgeoning food delivery industry present greater options for consumers.”

The report also noted increased interest in specialized and pre-mix flour for pastries and baked good and coatings for fried foods in the restaurant sector.

“In East China, there is even a growing trend toward home baking,” the report said. “As a result, demand has grown for high protein and low protein wheat imports as well as consumer expectations for higher quality standards.”

Trade war impact

Rice is a staple food in China, but the attaché pointed out that the country’s eating habits are changing and that with record stocks, the government is moving to reduce rice area. Farmers are being encouraged to switch to other crops, while using stocks of rice for starch or possibly ethanol production.

The attaché pointed out in an annual report published in March that China is the largest oilseed importer in the world.

“Rising incomes, urbanization and the modernization of the domestic feed and livestock sectors will continue fostering Chinese consumption of oilseed products,” the report said. “Growth in China’s oilseed production remains constrained by limited arable land and stagnant yield.”

However, an update report from the attaché, dated Oct. 30, 2018, forecasted that imports of soybeans and consumption of meal will stall in 2018-19, “due to ongoing trade tensions between the United States and China and an outbreak of African Swine Fever.”

Efforts are being made to resolve the dispute and Chinese imports of U.S. soybeans have resumed, following a meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping on Dec. 1, 2018, in the margins of a G20 Summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Negotiators from both sides met in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Jan. 30 and 31 as part of a series of talks taking place during a truce due to last until March 1, after which Trump has threatened to raise tariffs on Chinese products. Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, who led his country’s team in the discussions with U.S. officials led by Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, also visited the White House. Trump said following the meeting that “our farmers are going to be very happy.”

A side effect of the dispute has been to encourage China to cut soybean use for feed.

Biofuels and biotechnology

China has targeted the full implementation of E10 ethanol by 2020, but the attaché said in a report on the subject published in November that there are “numerous and significant challenges” to implementing the policy. The country wants to use biofuels as part of a strategy to conserve resources.

The attaché said in a report on biotechnology, dated Dec. 29, 2017, that “China is the largest importer of genetically engineered crops and one of the largest producers of GE cotton in the world, yet it has not approved any major GE food or feed crops for cultivation.” The report noted that the government had pledged to “push forward commercialization of new domestic types of Bt corn, Bt cotton, and herbicide-resistant soy by 2020, but no domestic event has received the bio-safety certificate necessary to commercialize.”

A report on the oilseeds sector published in March said that “currently, four soybean events are in the Chinese regulatory pipeline and under review for final approval.”