Brazil is one of the world’s biggest agricultural exporters, with the focus on its massive soybean crop as well as a large corn crop. A weak currency has helped Brazilian exporters remain profitable, while China’s tariffs on U.S. soybeans have diverted demand to the South American country.

The International Grains Council (IGC) forecasts Brazil’s total grains production in 2018-19 at 103.8 million tonnes, up from 88.2 million the year before. Production of wheat is put at 5.4 million tonnes, up from 4.3 million the previous year, while the corn crop is put at 95.1 million tonnes, up from 80.8 million the year before. The IGC forecasts 2018-19 sorghum production at 1.9 million tonnes, down from 2.1 million the prior year.

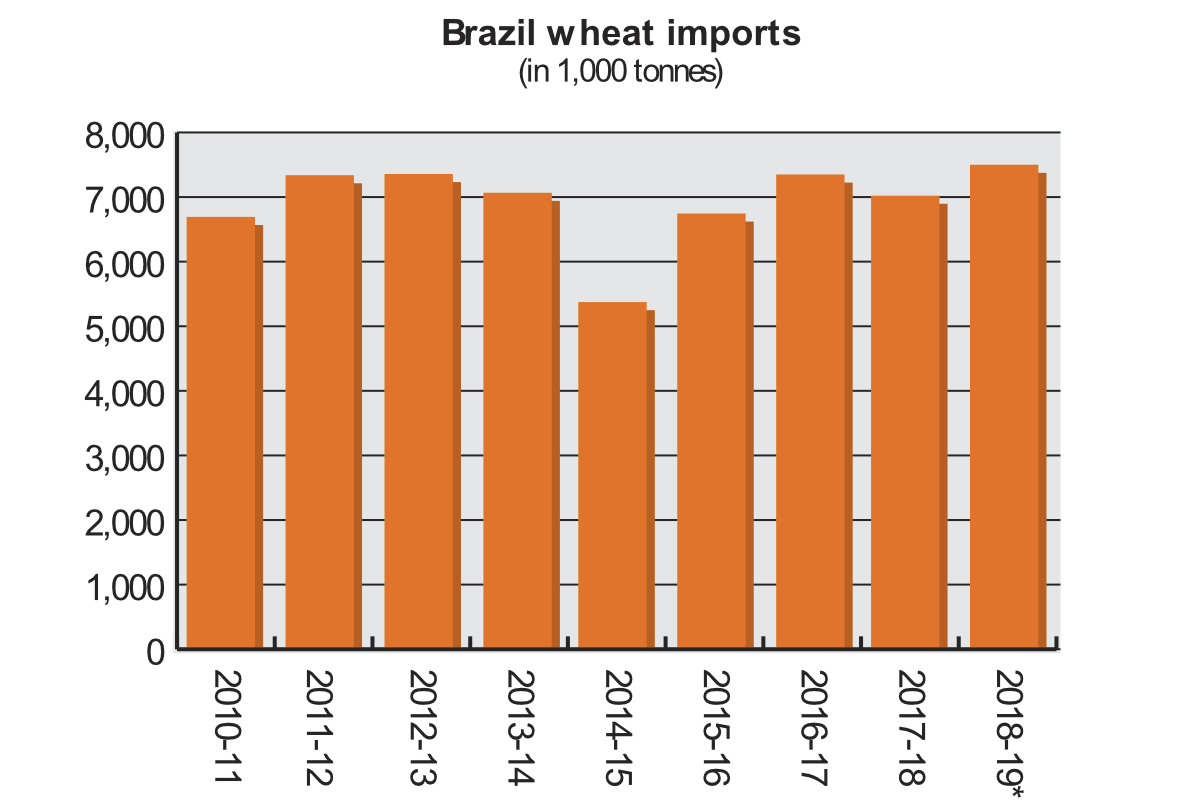

Brazil’s total grains exports in 2018-19 are forecast by the IGC at 24.7 million tonnes, down from 31.5 million tonnes in 2017-18, while its imports of grains are put at 8.8 million tonnes, down from 8.3 million the year before. Wheat is its biggest imported grain, with the IGC forecasting the total at 7.4 million tonnes in 2018-19 compared with 7.1 million tonnes the prior year. Brazil’s wheat exports are put at an unchanged 200,000 tonnes. Corn exports are put at 24.5 million tonnes in 2018-19, compared with 31.2 million the previous year, while imports of corn are forecast to come to 800,000 tonnes, up from 700,000 the year before. The IGC expects Brazil to import 600,000 tonnes of barley in 2018-19, up from 500,000 in 2017-18.

Brazilian rice production will be 7.8 million tonnes in 2018-19, compared with 8 million the year before, while its rice imports are put at an unchanged 700,000 tonnes and its rice exports are forecast at 800,000 tonnes, down from 1 million the prior year.

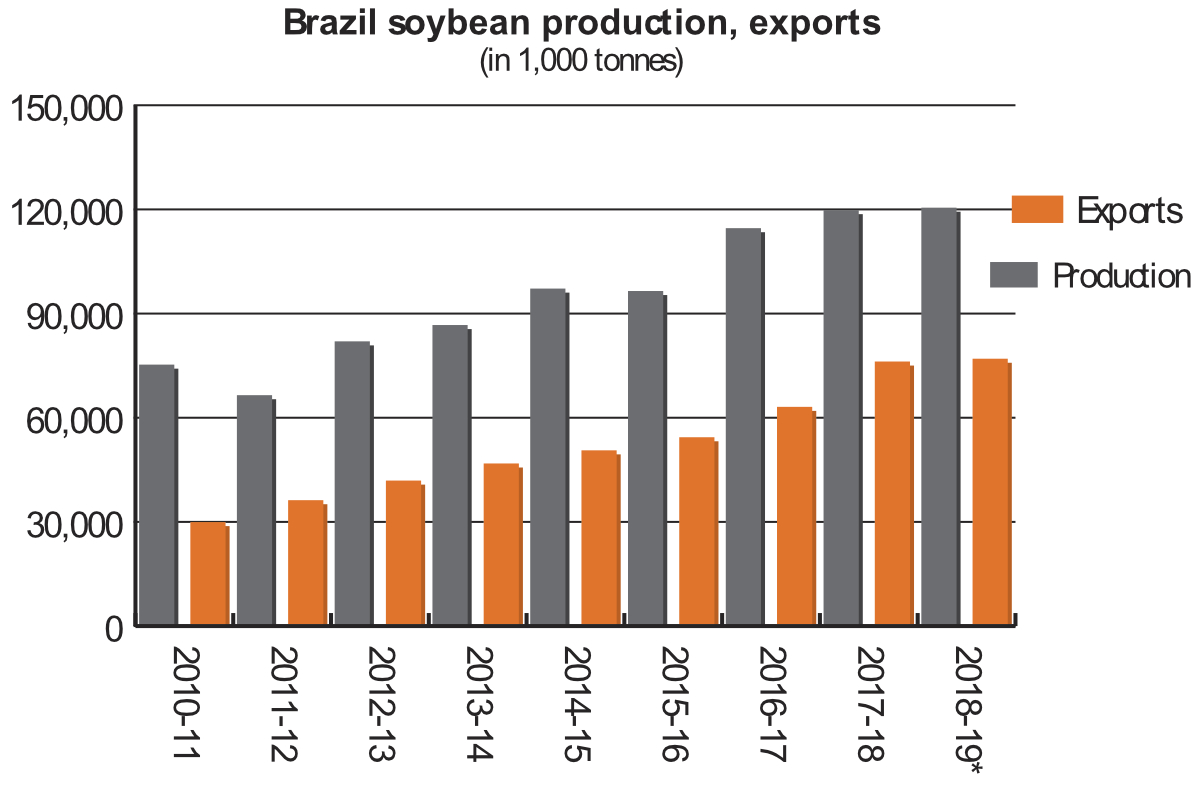

Brazil is a major producer of soybeans with the IGC forecasting its 2018-19 crop at 121 million tonnes, up from 119.3 million the year before. Brazil’s exports of soybeans in 2018-19 are forecast at 75.3 million tonnes, down from 76.2 million the previous year. Brazil also is expected to export 15.6 million tonnes of soymeal, down from 16.1 million in 2017-18.

Corn and wheat

An attaché report on the grains sector published in April explained that “most of Brazil’s first-crop corn is consumed domestically by the country’s large poultry and livestock industries, while the bulk of second-crop corn has traditionally been for export.”

The biggest export market, according to the attaché, is Iran, which was the destination for 16.5% of Brazilian corn exports in calendar 2017.

The report lists Egypt, Japan, Spain, Vietnam, and “other markets in Asia” as other export destinations. It describes Brazil’s corn imports as “negligible,” but notes that some small amounts come from Paraguay and Argentina to supply livestock operations in southern Brazil.

Brazil’s small wheat crop has been diminishing.

“Wheat area has been squeezed in recent years by expanding soybean hectares, as farmers try to increase revenue with a relatively more profitable crop,” the attaché explained. “Imported wheat makes up roughly half of Brazil’s domestic consumption, with most imports being duty-free purchases from MERCOSUL-partner Argentina.”

Flour Milling and Rice

According to the Brazilian flour millers’ association, Abitrigo, there were 203 mills in operation in Brazil in April 2018, with 81% of them being described as industrial. In 2017, Brazilian mills put 7.964 million tonnes of wheat flour on the market, with consumption per person in the country put at 40.5 kilograms.

“Brazil generally imports higher-quality wheat so that millers can blend it with domestic supplies to achieve the desired flour quality for bakeries to make small crusty French-style baguettes (pão francês),” according to the attaché. “This type of bread is a Brazilian breakfast staple, usually consumed with butter, cheese, cold cuts and coffee.”

The attaché explained that “rice is a staple food in Brazil, with most Brazilians consuming it one to two times daily.”

“Total rice area in Brazil has declined for eight of the last 10 years, with rainfed area seeing the largest declines, as rice is replaced with more profitable crops like corn or soy,” the attaché said. “The vast majority of Brazil’s rice imports come in duty-free from its MERCOSUL neighbors Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina. Most of Brazil’s rice exports are bound for other countries in the Western Hemisphere or Africa.”

Soybeans

In an update in October, the attaché explained that an increase in the planted area for soybeans for 2018-19 is due largely to optimism among producers about prices and despite disruptions to fertilizer deliveries resulting from a truckers’ strike in May.

“Since the beginning of the calendar year, local soybean prices rose markedly on the back of robust demand from China, as well as the weak Real (R$),” the report said. “In the wake of U.S.-China trade tensions and following implementation of a 25% duty on U.S. soybeans by China in April, Brazil saw a surge in Chinese demand for its crop.”

Had China continued to import U.S. soybeans, the attaché suggested, the dollar price for both Brazilian soybeans would have been lower.

“Even in this scenario, Brazilian producers would have still seen strong returns due to the plunging value of the domestic currency,” the report said.

“The fact that China has been buying Brazilian soybeans so strong means that Brazilian stocks will remain fairly low, hovering around 1% of domestic supply for MY 2017-18, as well as in 2018-19,” the attaché reported. “In Post conversations, sources did not express any concern regarding the low stock to domestic supply ratio.

“The assumption in Brazil is that should there ever be a shortfall for domestic consumption, Brazil could always bring in additional supply from neighboring producers. Instead, traders and producers alike are clearing out every last bin in order to take advantage of the upside in prices stemming from international trade tensions.”

Biotech and Ethanol

An attaché report, published December 2017, pointed out that Brazil is the second largest producer of biotech crops in the world, putting the adoption rate for corn, soybeans and cotton for the 2017-18 crop at 81% of planted area.

“As of Nov. 17, 2017, there are 68 GE events approved for commercial cultivation in Brazil, of which 39 events are for corn, 15 for cotton, 11 for soybeans, one for dry edible beans, one for eucalyptus, and, most recently, one for sugarcane,” the report said. “GE events with herbicide tolerance traits lead the adoption rate with 65% of the total area planted followed by insect resistance with 19% and stacked genes with 16%.”

Brazil has been an enthusiastic adopter of ethanol, but its national program has been based on sugarcane. However, the attaché has reported that in August 2017, FS Bioenergia, a joint venture of Iowa-based Summit Agricultural Group and Brazil-based Fiagril, began commercial operations at Brazil’s first corn-only ethanol plant in Lucas de Rio Verde, Mato Grosso (most ethanol plants in Brazil process only sugarcane or a mixture of corn and sugarcane).

At the time of the report, the plant was being reconstructed to raise its capacity so that it could process 1.26 million tonnes of corn each year to produce 530 million liters of ethanol, along with 400,000 tonnes of distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS), and 15,000 tonnes of corn oil. Additional plants were being planned.

“While corn ethanol production still accounts for only a tiny fraction of Brazil’s overall ethanol production, the abundant supply of corn and growing domestic demand for ethanol, especially in the center of the country where gasoline prices are higher, likely mean that Brazil’s corn ethanol production will continue to expand,” the attaché said.